In 1683, the most dangerous man in the world escaped from England to the Netherlands.

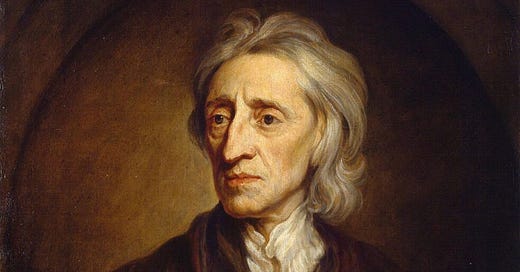

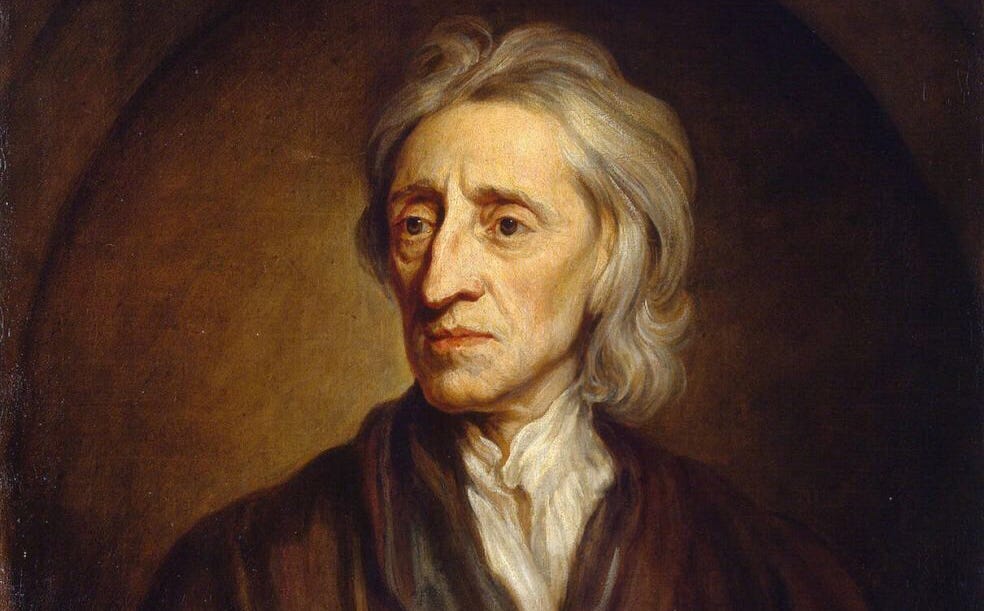

He didn’t look very formidable. He was 51 years old, lanky, and asthmatic. He had, according to one description, a “long face, large nose, full lips, and soft, melancholy eyes.”

Yet the King of England considered him one of his deadliest enemies. As the right-hand man of Charles II’s chief political opponent in the country, he was suspected of conspiring to assassinate the king.

But what really made him a threat to the throne was not his skill in the lethal arts, but his genius in the literary arts.

In the hand of John Locke, the pen was truly mightier than the sword.

Locke sailed out of England with a powerful weapon: one that would eventually overthrow, not just one monarch, but all of them. That weapon was a book, at that point an unpublished draft: Two Treatises of Government.

That book was a systematic philosophical case for liberty. Locke knew that his anti-absolutist book might get him killed by England’s absolute monarch. Indeed, later that year Locke’s ally Algernon Sidney was executed for treason, and Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government were cited as evidence in his trial.

So Locke did not publish his Treatises until 1689, the year after Charles’s successor James II was deposed in the “Glorious Revolution”—and even then, only anonymously. Locke publicly denied authorship throughout the rest of his life, only admitting it in his will. Locke died in 1704.

Later in that century, the ideas in Locke’s Two Treatises of Government became the elements of America’s founding philosophy:

Equality, in the original sense, not of equal abilities or equal wealth, but of non-subjugation;

Inalienable Rights, not to government entitlements, but to life, liberty, and property;

Democracy, in the original sense, not of mere majoritarian voting, but of popular sovereignty: the idea that governments should not be masters, but servants of the people;

Consent of the Governed: the idea that governments can only legitimately govern by the consent of the governed, i.e., the sovereign people;

Limited Government: the idea that the sole purpose and proper scope of legitimate government is only to secure the rights of the people;

The Right of Revolution: the idea that any government that oversteps its limits and tramples the very rights it was charged with securing is a tyranny, and that the people have a right to resist, alter, and even abolish tyrannical governments.

These ideas animated the American Revolution and permeated the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The enormously successful American experiment caused the global prestige of Lockean political philosophy to soar. As Locke’s political principles were adopted throughout the world, liberty spread and absolutism receded.

The ideas contained in the papers that John Locke smuggled across the water from England in 1683 turned the world upside-down: or rather, right-side-up.

This wondrous achievement for humankind has since been partially reversed in many ways. Enemies of liberty have twisted Locke’s terms to pervert their meaning and serve modern variants of absolutism.

But world history took a much freer course because Locke lived, thought, wrote, and published.

Whether he knew it or not at the time, John Locke was the most dangerous man in the world as well as the most heroic: a menace to tyrants and a liberator of generations.

For more on John Locke’s life, works, and influence, read Jim Powell’s wonderful profile, “John Locke: Natural Rights to Life, Liberty, and Property.”